Arts

Indian-Australian Playwright Pratha Nagpal’s ‘Maa Ki Rasoi’ is a Love Letter to Her Mum

In conversation with South Asian Australian Pratha Nagpal on her latest play ‘Maa Ki Rasoi’ (My Mother’s Kitchen).

Australia abounds with emerging South Asian talent. Young creatives, like Indian-Australian playwright Pratha Nagpal, are infusing the landscape with fresh, authentic voices that mirror the complexities of their multicultural identities.

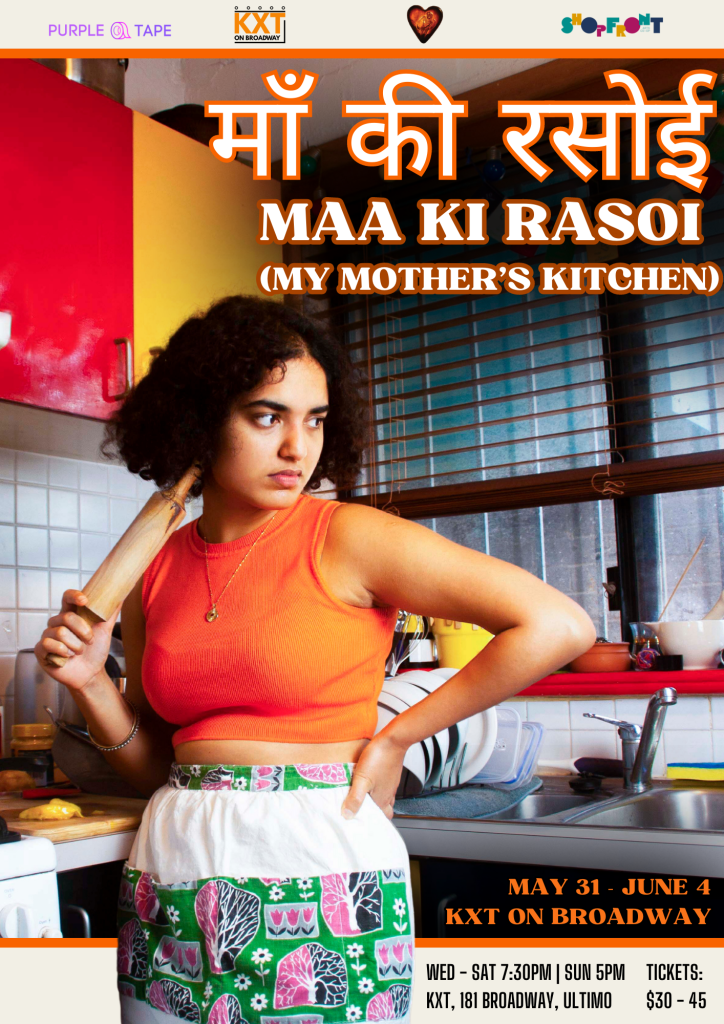

Pratha’s latest work, Maa Ki Rasoi (माँ की रसोई – My Mother’s Kitchen), is a stirring tribute to a mother’s love, a reflection of the immigrant experience and the struggle of straddling two cultures. The play, which began as a project for ArtsLab’s residency program and has since been showcased at 107 Redfern and the Art in the Heart of Haymarket Festival, is returning for its third season at KXT on Broadway (Ultimo, Sydney/Eora) from 31 May 2023 to 4 June 2023.

Maa Ki Rasoi was written and directed by Pratha Nagpal and will be performed by Madhullikaa Singh. Pratha probes her disconnection from domesticity, the “intergenerational guilt of the loss of culture”, and the “deep yearning for the feeling of home”. In short:

Maa Ki Rasoi is about many things, but ultimately is a love letter to my mum—from her daughter, who cannot cook.

Pratha Nagpal

The stage is set, the kitchen is abuzz, and the curtain is about to rise on Maa Ki Rasoi. Brown Boy Magazine managed to steal a moment with Pratha to discuss the inspiration behind Maa Ki Rasoi, her experiences as a South Asian Australian in theatre, and how she navigates her hybrid identity within her creative work.

Our conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

Brown Boy Magazine: Who is Pratha Nagpal? Can you tell us a bit more about yourself? Growing up, how did your South Asian heritage shape your perspective on the arts, especially theatre—considering that it’s your career now?

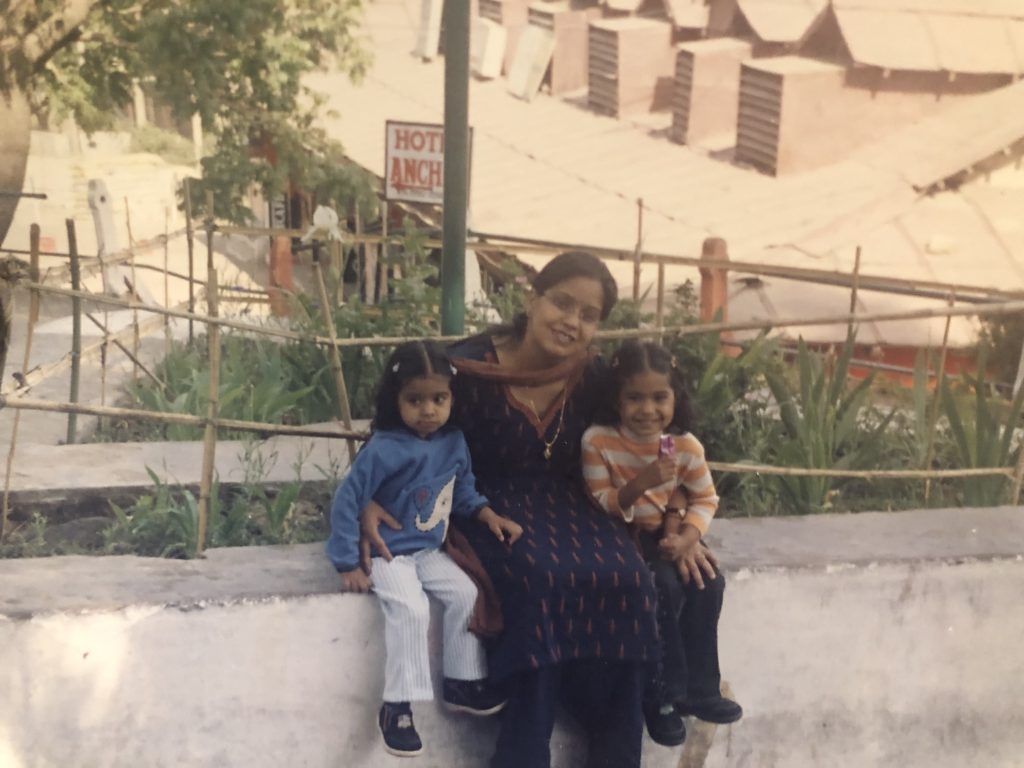

Pratha Nagpal (PN): So, I was born in New Delhi and moved to Sydney when I was 12. I loved my upbringing in India. I was very privileged to grow up in a family where I felt protected and had a good education. In our summer holidays, my parents would take us to museums and art exhibitions, and I fondly remember being exposed to the arts. However, I never really saw myself being an artist.

Living in Delhi as a young person, I was exposed to the city’s vibrancy, and when I moved countries, I spent a long time (still do) missing the same vibrancy. So I think that has influenced my theatre-making because there was nothing I saw that was capturing this feeling of home, and I felt like I had to create it for myself.

BB: Could you tell us a little bit more about Maa Ki Rasoi? What’s the catalyst that set you on the path to writing the play?

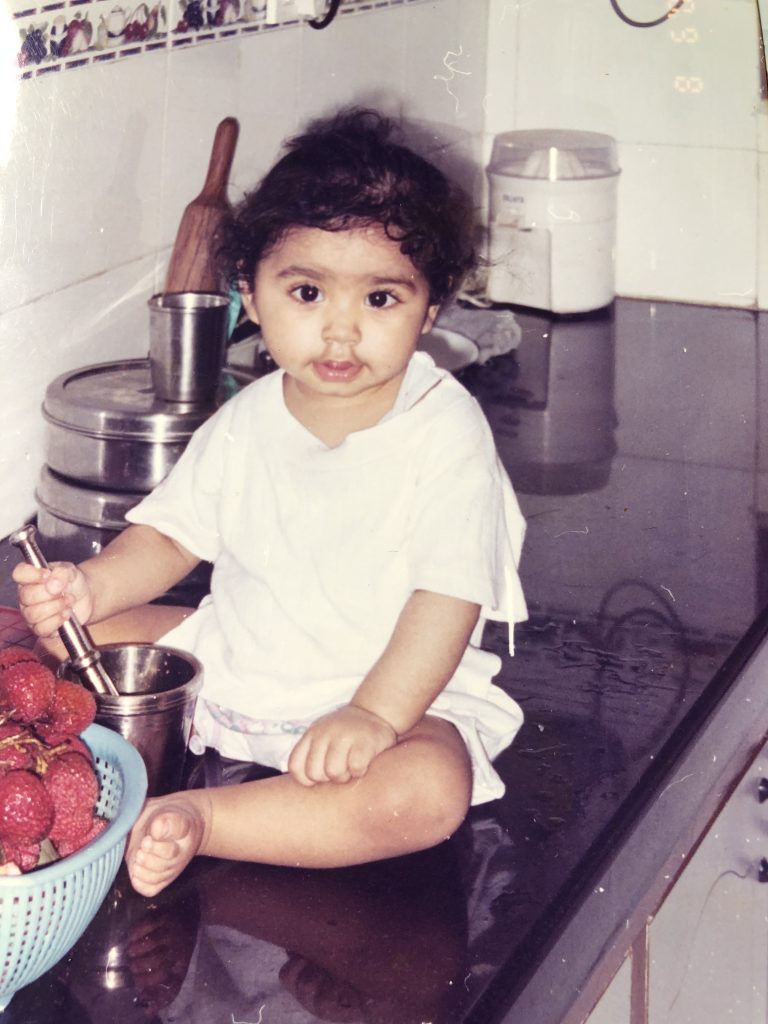

PN: Maa Ki Rasoi started as a play I wanted to write to celebrate my mom. I wanted to do justice to all her sacrifices for our family. At the conception of this idea, I was assistant directing a show meant to explore intersectional feminism. Still, I found myself time and again wondering if I’d call my mother a feminist. I realised in that incredibly white space, I had to justify my mother’s feminism, and it bothered me. So, I started writing Maa Ki Rasoi.

It’s a play about failing to write a play about my mother. I explore the fear of failing to celebrate the powerhouse that my mother is because I fear that the West will reject it. In that exploration, I open what feels like a pandora’s box of feelings and emotions in an attempt to articulate my broken relationship with the kitchen, domesticity and the push and pull of identity and culture.

Maa Ki Rasoi is about many things, but ultimately is a love letter to my mum—from her daughter, who cannot cook.

BB: What do you hope your audiences will take away from Maa Ki Rasoi?

PN: When writing the work, I was adamant about describing the target audience as my mother. I wanted to write a play for my mum and my mum only. I wanted her to watch a theatre piece and like it (my mother clearly has high standards, haha). But the more I was immersed in the process, I realised I wasn’t writing a play about my mum in isolation; it was about unpacking my complex relationship with my mother. So, I ended up wanting to make immigrant children and mothers feel seen through my work. I think the theatre industry is notoriously comfortable with forgetting to tell stories for and about us, and I wanted to change that.

So, all I want audiences to do is give their loved ones a call or a message as they walk away from the work. Or better yet, bring them to watch the show together!

BB: How have you navigated the challenges of representing South Asian stories in a theatre landscape where they have historically been underrepresented? What changes would you like to see for South Asian representation in Australian theatre?

PN: As a 21-year-old emerging artist, I have barely navigated the challenges of representation. It’s a very heavy weight to carry and terrifying to face.

That’s what the fear of representation is—this feeling that somehow you’re doing it wrong. I was extremely nervous about writing a play about a brown woman in the kitchen because that’s every racist stereotype ever. Brown women are just seen to be the face of domesticity, and I was so scared to be a brown woman and fall into the trap of doing harm to my own community.

When the landscape is so white, not just in its faces but its structures too, your existence and voice threaten their foundation, and feeling like a threat is an isolating feeling. But the strength in all this is that you find community—you find others who are fighting the same fight, and you join forces—and it’s a good feeling. And the truth is that the landscape is changing. We have a long, long way to go, but we are creating new structures and shifting the pre-existing ones, and while it’s a hard battle, change is happening.

BB: Do you have any advice for South Asian Australian writers and directors?

PN: My advice to other BIPOC creatives would be what I’ve been told my whole career—tell the stories that scare you because those are the stories that mean something to you. When Maa Ki Rasoi first debuted, I was incredibly scared to be this vulnerable with so many people, but more than that, I was afraid that no one would understand my story, and I would walk away feeling very alone.

But there is power in being vulnerable in our storytelling, and while it’s so scary, it’s part of our effort to change the landscape. We have to tell our truth, not in a pushy way—take your time, but tell your truth. And the community you find becomes your support system and cares for you when you feel the burden of representation because, honestly, there’s not much escaping that.

BB: Maa Ki Rasoi translates to ‘My Mother’s Kitchen.’ Any cherished memories from your own mother’s kitchen?

PN: My cherished memories in the kitchen are just the laughter and chaos that unfolds. A lot of my relationship with my mother has been built in this space. It’s where we sing songs, gossip, and have a lot of our important conversations. So really, it’s this holistic purpose that the kitchen serves for our relationship that I cherish a lot.

Brown Boy Magazine (@brownboyau) celebrates worship-worthy tastemakers and changemakers in the South Asian Australian diaspora (without taking itself too seriously).

You may like

Here Are Some Shows by South Asian Creatives to Catch at the Melbourne Fringe Festival

South Asian Australian Shamita Siva Showcases Her Versatility In Vidya Rajan’s Dark Comedy ‘Crocodiles’

‘It’s a Good Time To Be a Brown Woman’: Sri Lankan-Australian Comedian Sashi Perera On Her Debut Solo Show ‘Endings’, Backing Yourself, and Why Internet Trolls Should ‘Just Have A Maz’